- Home

- A. S. Dagnell

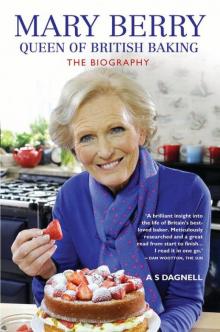

Mary Berry

Mary Berry Read online

For Mum, Dad and Nicole

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

SOURCES

I have drawn on various newspaper articles from the last 30 years as part of my research for this book. In particular the following newspapers and their supplements have been particularly helpful: Daily Mirror, Sunday Mirror, Daily Mail, Mail on Sunday, Daily Telegraph, Sunday Telegraph, Daily Express, Sunday Express, Financial Times, Independent, Independent on Sunday, The Times, Sunday Times, Guardian, New York Times, Scotsman, Bath Chronicle, Western Morning News, Gloucestershire Echo, Bucks Free Press Broadcast, Kent Messenger, London Evening Standard, The Journal, Leicester Mercury, Press Association, Brentwood Gazette, Essex Chronicle and The Grocer.

On top of that I have drawn from Mary’s appearance on BBC Radio 4’s Desert Island Discs in 2012 as well as various interviews published on different parts of the BBC’s various websites on a number of occasions. Her interviews with ITV News were also very helpful. Her appearances on Great British Bake Off have, of course, been a rich source of information and anecdotes, particularly in writing the latter chapters of this book.

A number of other websites and blogs have been useful sources of information in building a picture of Mary’s colourful and exciting life. These include her own website MaryBerry.co.uk, TVCream.co.uk, Wikipedia, YouTube, the websites of the Child Bereavement UK and National Osteoporosis UK charities, the AGA company’s official website, The World According To Lady Gaga blog and the hilarious Mary Berry Biting Into Things blog, as well as various BBC websites and the World of Books blog.

THANKS

Special thanks have to go to Kat Lay, a brilliant journalist and friend who helped me with the extensive research of this book. She helped me by ploughing through the newspaper archives, transcribing interviews with Mary and digging out as much information on Mary as she could find. Thanks Kat, I couldn’t have done it without you.

Many thanks go to Clive Hebard, who has edited this book. Your guidance, experience and insight have been invaluable and I couldn’t have done it without your help.

Also thanks to all my friends who have given me support while writing the biography. In particular Matt Sandy, Donna Bowater, Emma Barrow, Tom McTague, Sian Cox-Brooker, Jonathan Theodore, Sofia de Speluzzi, Martin Brown, Halina Watts, Dan Wootton, Matt Thomas, Sian Grieve, Claire Rees, Lorna Prichard, Ben Glaze, Mandy Lau, Sarah Arnold and Jill Main.

Huge thanks also to everyone at the Sunday Mirror for their words of wisdom and advice while I was writing. My bosses Caroline Waterston and Claire O’Boyle, thanks for being patient and helping me out. Also Alison Phillips, Gary Jones, Deirdre O’Brien, Ben Griffiths, Justin Penrose, Will Payne, Dean Piper, Hannah Hope, Dominic Herbert, Francesca Cookney, Sarah Turner, Marjorie Yue, Zena Alli, Justine Naylan and Jolene Dearsley.

And most of all thanks to Dad, Mum and my sister Nicole for all the extra help and support as well. Thanks for putting up with me.

CONTENTS

Title Page

Dedication

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

CHAPTER 1 MARY’S STAR RISES

CHAPTER 2 EARLY LIFE

CHAPTER 3 COOKING ON GAS

CHAPTER 4 FAMILY MATTERS

CHAPTER 5 SAVED BY CAKE

CHAPTER 6 QUEEN OF THE AGA

CHAPTER 7 FROM BAKING TO BROADCASTING

CHAPTER 8 LET THE BAKE OFF BEGIN!

CHAPTER 9 THE BAKE OFF CONTINUES

CHAPTER 10 THE QUEEN OF BRITISH BAKING

Plates

Copyright

CHAPTER 1

MARY’S STAR RISES

As Mary Berry took a bite out of Janet Basu’s croissant, you could have cut the atmosphere with a knife. Four contestants were vying for a place in the prestigious final of one of the year’s biggest reality TV shows – and everything was to play for. The winner would have the honour of being crowned the greatest amateur baker in Britain, and this would open up endless possibilities for them. The previous winner of the show had secured a baking book deal, the chance to tour the country showing off their skills, and even the opportunity to develop their own line of baked goods. The contestants knew the possibility of taking their love of baking to the next level was within their grasp. The pressure was on, with an audience of millions watching the contestants’ every move with baited breath, anticipating which one of the four would falter at the last hurdle and who would make it through. Loyal fans of the series also knew to watch the judges closely, too, as it all came down to Mary’s verdict – what she thought of the buttered, savoury treat that the former French teacher had baked for her. The nervousness on Janet’s face was plain to see. Was the croissant too crumbly? Had the heat from the studio lights affected the end result? Was the texture of the pastry right? Or had she used too much butter?

The suspense was such that it would have been easy to imagine that this was the climax of a singing competition like ITV1’s The X Factor or even BBC1’s long-running ballroom dance show Strictly Come Dancing. But in fact this was the Great British Bake Off, the BBC2 cookery show that was in its second series and heading towards the final. And just like Britain’s Got Talent and Strictly, competition and high drama fuelled the show, only with the carefully rehearsed songs and meticulously choreographed dance routines replaced … by baked goods.

A surprise hit, the show had blossomed in the year following its first series. Viewing figures had risen from a respectable 2.2 million to in excess of 5 million – a considerable feat for any TV cookery show. After first airing in August 2010, it was safe to say the show had become a veritable triumph, a runaway success; it had become much more popular than its producers could have hoped. No one, not even the creators of the show, could have predicted that so many people would become hooked on a competition revolving around the humble art of baking.

But hooked they were. The ingredients of the show’s success were very simple. After a rigorous selection process, a total of 12 home bakers started out at the beginning of each series. They then went head to head against one another, battling it out to be handed the coveted title of Britain’s best baker at the end. Week after week they were put through their paces, as they were given three classic British baked products to impress the judges with. Everything from profiteroles to pork pies was produced in vintage-style village marquees, with the challenges becoming increasingly difficult as the series progressed.

To make the competition as tough as possible, each week the contestants would have to produce three bakes. First they had to cook up a signature bake, to show off their tried-and-tested hand-cooked treats. Next came the technical bake, during which every baker cooked from the same recipe – turning the kitchen into a level playing field but pushing many contestants out of their comfort zone. Then finally the contestants were really put to the test with a show-stopper, allowing them to show off their individual flair and creativity as they produced elaborate creations that really played to their strengths and tested the depth of their individual skills.

On top of the cooking, to add an extra dimension to the show, it was decided that the programme would trace the rich history of British baking by having each episode filmed at a different baking landmark. When Bakewell puddings were on the menu, the competition fittingly moved to Bakewell in Derbyshire, where the eponymous tart was first made by accident in 1820, by a chef at a pub called the White Horse Inn, after he messed up a recipe given to him by the landlady. Mini documentary-style films about the history of baking were also woven into the show.

It sounds nice and genteel – but, of course, this was also a competition. Each week the contestant whose culinary skills were most lacking was ejected from the show, until the 12 were whittled down to a single winner. There were tears over the tinfoil, curses into the clingfilm and breakdowns by the b

aking trays. The gentle pursuit of baking got the full reality-show treatment.

It was a formula that had worked so well before, and the producers hoped it would mirror the success of other competitive cooking shows. The long-running MasterChef, which was on screens in the UK from 1990 for 11 series and later revived in 2005, had been syndicated across the globe in places as far-flung as Vietnam, Indonesia and Bangladesh. Other programmes such as ITV1’s Hell’s Kitchen had also been a ratings hit – celebrities had been pitted against each other in makeshift restaurants run by TV chefs Gordon Ramsay and, later, Marco Pierre White. Combining cooking and reality TV was proving to be a sure-fire ratings hit, and was a format that BBC commissioners felt they could take in an interesting direction. But this time it was to be different. Elaborate nouveau cuisine would be replaced with scones, Victoria sponges and treacle puddings. What wasn’t to like?

But few could have anticipated that the show would become so universally loved, as quickly became the case. But while the contestants became mini-celebrities in their own right, the real fame – it would soon become clear – was reserved for the judges. As was often the case with reality shows, it was the judges who emerged as the actual stars.

When it came to picking them, it had been important to strike the right balance. Producers wanted two judges who really knew their stuff. The first to be chosen was a former professional baker, Paul Hollywood. As a man who knew his trade like the back of his hand, after learning from his father (who was also a baker), it was envisaged that Paul would be able to dispense honest advice and criticism without any showbiz airs and graces. He would be cast as the no-nonsense judge who wasn’t afraid to speak his mind and throw the occasional witty put-down in the direction of an unfortunate contestant whose talents had gone awry. This was a familiar role, well defined by other competitive cookery shows. For example, MasterChef had Gregg Wallace, the shaven-headed restaurateur who was born and raised in the East End of London and began his career selling vegetables at a stand in Covent Garden. He regularly referred to himself as ‘the fat, bald bloke on MasterChef who likes pudding’, pulled no punches when it came to speaking his mind, and had proved incredibly popular. Similarly, Gordon Ramsay’s TV career had flourished thanks in part to his uncompromising perfectionism and infamous short temper on Hell’s Kitchen, his first prime-time reality show. His use of expletives during confrontations with contestants paid no heed to the fact that they were celebrities. The concept of a mercurial, mouthy chef daring to flamboyantly criticise famous soap stars, singers and actors for producing below-par food was lapped up by viewers. And so, with his straightforward and honest manner, Paul Hollywood would fit the bill for Bake Off perfectly, the producers decided.

However, the producers also wanted someone to complement Paul … someone familiar to viewers; a sympathetic character who knew what they were talking about, but who could also let the contestants down gently when their baking wasn’t up to scratch. There needed to be balance – a gentler, female presence on the show; a person who was equally capable in the kitchen but perhaps a touch more diplomatic. After much brainstorming, the producers kept coming back to one name – Mary Berry.

This world-renowned and celebrated cookery writer was loved and respected by the British public in equal measure. Since the late 1960s Mary Berry’s books had flown off the shelves. She had written more than 70 titles, which between then had sold in excess of 5 million copies. She had become a popular fixture on TV and radio, dispensing advice to would-be homemakers and carrying out cookery demonstrations. She had written widely for newspapers and magazines across several decades. She was the so-called Queen of the Aga, having run cookery classes custom-designed for the iconic stove from her own kitchen. On top of that, she had travelled the length and breadth of the country, cooking for live audiences, as well as lending time to support her favourite charities. Baking, she said, had helped her through some of the hardest times in her life as well as helping her celebrate some of the happiest. And as a trusted, kind woman in her seventies, she had wide appeal across the age groups, right up to the older demographic the show was hoping to capture. Mary Berry seemed like the perfect choice of presenter.

To the producers’ delight, Mary agreed and signed up for the show.

It would be her job, alongside Paul, to taste the recipes and help give feedback to the contestants. The two would also have the final say on who stayed each week … and who went. Their partnership seemed to work instantly and they appeared to complement each other perfectly. Many television critics agreed that the chemistry between Mary and Paul made the show an instant success. Reviews were overwhelmingly positive. And Mary, who had been off TV screens for some years, and busy writing more and more cookery books, was suddenly reinvented as a prime-time star. She took to the role like a duck to water and appeared to have the critics eating out of the palm of her hand.

‘Mary has firmly established herself as the doyenne of cakes and no-frills Aga cooking,’ Sarah Rainey wrote in the Daily Telegraph. ‘The true star of the Great British Bake Off, she has captured the hearts of millions with her polite, no-nonsense judging style, critiquing contestants’ “soggy bottoms” and “uneven bakes” – but always with a smile.’

Michael Hogan in the Observer was also adamant that Mary was the stand-out star. ‘The Great British Bake Off proved a surprise hit last autumn, pulling in 5 million viewers,’ he mused. ‘Its queen bee is food writer Mary Berry. This doyenne of dough has had her face pressed to the oven door for 50 years and has published 40-plus cookbooks. She and co judge, the brilliantly named Paul Hollywood, get down on their haunches to peer at contestants’ confections, poke them to rate “the quality of the bake”, then diagnose faults with forensic honesty. Berry is unfailingly polite, deploying a withering look of disappointment, like a badly let down home economics teacher.’

And the praise just kept coming. Sadie Nicholas in the Daily Express was equally gushing. She wrote: ‘It’s become something of a guilty pleasure, for the Great British Bake Off is deliciously moreish, feel good television at its best. However, unlike other competitive and highly successful food programmes – MasterChef and the Great British Menu to name but two – GBBO offers something altogether more, well, British and genteel, its format evoking images of village fêtes and afternoon teas. Nostalgia plays a huge part in the success of the programme … After all, baking was the first experience that many of us will have had in the kitchen as children.’

As if that wasn’t enough, Vicky Frost in the Guardian added: ‘Judges Mary Berry and Paul Hollywood come from the tough but fair school of television experts. There is little emotional discussion of the contestants’ journey to get this far in the competition, it is entirely about the bake … Berry can spot an incorrectly rolled roulade at 20 paces. Both provide masses of hints and tips for getting it right.’

High praise if ever there was any. But while the critics were unanimous, so were the viewers. A search of Mary Berry’s name on Google returns no fewer than 33.6 million results, with hundreds of fan pages cropping up across the Internet, including on popular social networking sites such as Facebook. ‘She’s such a lovely woman, like the best grandmother in the world,’ says one fan. Another adds: ‘How can anyone be 77, make a living eating cake and look that good in jeans?’ One blogger has even dedicated a whole site to photos of Mary biting into cakes; such is the obsession with TV’s most unlikely star. Captions on the blog include: ‘Now here’s a rare bite for you to check off in your I-Spy book of British Bites. Here, Mary uses her little-documented telepathic power to orchestrate a beautiful synchrobite with the all-too-susceptible Paul.’ It’s fairly apparent that the website is to be read with a large dose of irony. But it indicates just how large Mary’s cult following has become. And this fan base looks set to grow as the Great British Bake Off continues its run.

But while Mary’s star was on the rise once again, it appeared that Janet’s croissants hadn’t risen quite as she had hoped. Alongside hou

sewife and grandmother-of-three Janet Basu, who hailed from Southport, Merseyside, were Mary-Anne Boermans, Holly Bell and Joanne Wheatley. All of them had sweated blood and tears to get to this stage and, during that process, Janet had emerged as the favourite. Viewers adored her, not least because of her down-to-earth personality. When contestants had to make pork pies with quails’ eggs, Janet made no bones about the fact that she had simpler tastes. ‘I’m not grand like Henry VIII, living on quails’ eggs and larks’ tongues,’ she said. And she had been self-deprecating while comparing herself to her rivals. ‘Jo was sitting there looking demure and elegant before I’d even crushed my silly biscuits,’ said Janet, referring to Joanne, who would eventually go on to triumph and win the second series. In the world of fly-on-the-wall TV, Janet was a viewers’ favourite – someone whom they could empathise with.

Her personality aside, Janet’s skills in the kitchen were brilliant too. Her cheesecake reigned supreme, her cookies were the best by far and her torte was good enough for a Michelin-starred restaurant, she was told. But then something went wrong. As she approached the finish line, problems emerged. Her chocolate roulade, a tricky recipe for even the most seasoned of bakers to get right, disintegrated into a mound of crumbs. She was given a second chance and it all came down to her final dish – pastries. And as Mary Berry tasted them it was clear she wasn’t impressed. Janet’s iced buns and croissants were ranked bottom out of the four contestants. In her typically droll fashion, the show’s co-presenter Mel Giedroyc said that Janet’s croissants ‘look like a neck support’. The writing seemed to be on the wall for Janet. Despite all the good she had done up until that point, the judges’ decision was final. She was sent home, hanging up her apron and turning off her oven for the last time.

Mary Berry

Mary Berry